Background

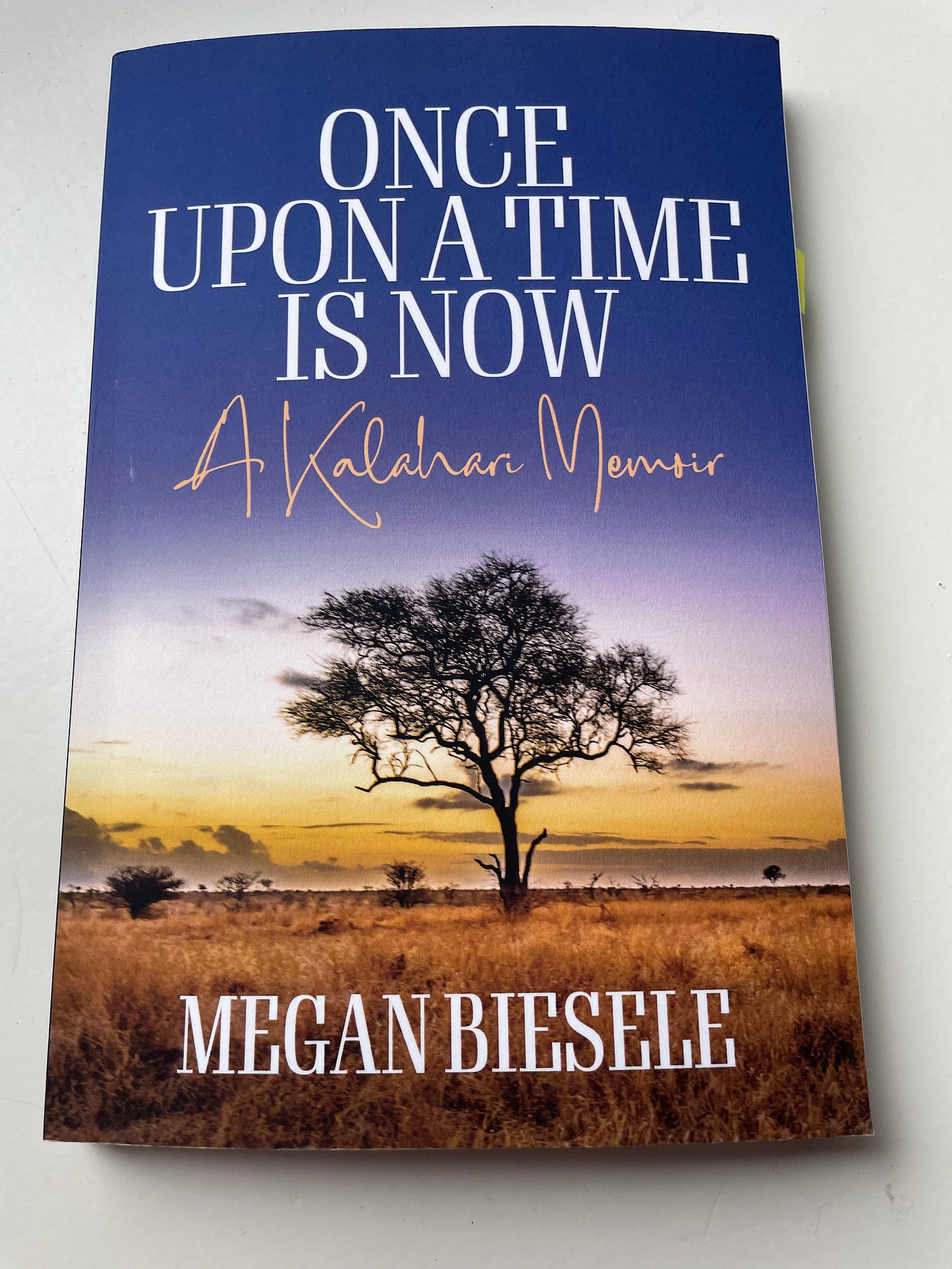

Megan Biesele is an anthropologist whose life and learning make me wish I’d been one. Her latest book, Once Upon a Time is Now: A Kalahari Memoir, is about her first fieldwork experience in 1970. Primary among these experiences with people who hunted and gathered in a desert, were the folktale telling and the healing dances of the Ju|’hoansi, both powerful tools for enabling social cohesion, Megan believes.

I gobbled up the book, wishing it had been written 30 years ago when I started my quest to learn more about the indigenous group of people called the San. It’s written with Megan’s characteristic intellectual insight, elegantly phrased, precisely worded and rich with her generosity of spirit. It’s honest about the dark days she endured exhausted by doubt, demands made upon her and frustration due to her initial lack of linguistic and cultural comprehension. Finally, it’s an acknowledgement of the epiphanies the experience awarded her.

In an accessible way she presents the lessons she learned as both a human and an anthropologist, from the Ju|’hoan people.

The bonds she forged set her upon the path of advocating for San rights. For example, in 1973 she co-founded the Kalahari Peoples’ Fund, an important non-profit still active today. She also worked as translator for the Ju|’hoansi during the Namibian land rights conference. She has encouraged and assisted countless Kalahari fieldworkers, including me, and facilitated cultural awareness visits by San friends to other parts of the world. One of my favourite anecdotes is about an exchange between Kiewiet, a renowned healer, and a member of his American audience:

“You said that you travel to God when you are in trance and are healing. Please tell us what God looks like.”

Kiewiet chuckled. “I have never seen God. Nobody can see God. All that human beings have is stories.” (p. 166)

Recently, Megan donated her valuable collection of Ju|’hoansi recordings to the Endangered Languages Archive, complete with transcriptions made by native speakers she trained. (One of whom is |Ai!ae Fridrick |Kunta who transcribed ‘Chief’ Bobo’s blessing.)

Q & A

1. Of which San-related project that you’ve spear-headed/supported, are you most proud, and why?

“I am most proud of the Ju|'hoan Transcription Group (JTG) I initiated in 2002 in Namibia. An outgrowth of the Village Schools Project that enabled the growth of mother-tongue literacy in the Ju|'hoan language, the Transcription Group provided computer literacy and training in the use of a state-of-the-art transcription software, ELAN, developed in the Netherlands. Using this tool, native Ju|'hoan-speakers have produced and published authoritative written records of voice recordings made of their own community's folklore, songs, speeches, and meetings. These written records in turn have enabled schoolbooks and archives for the Ju|'hoan community in both Namibia and Botswana, and have provided first-class research materials for scholars studying the linguistics and verbal art of this still-thriving click language. I believe the JTG has played a role in the creative survival and lively current use of this once-endangered language.”

2. You wrote: “Bushman practice humanism every day.” Please say more.

“I think of ‘practicing humanism’ as, broadly, relying on time-honed spiritual, intellectual, and economic human social activities to solve the problems of everyday living. Some of the Ju|'hoan people's problems have been around for millennia, and some of them are new ones, created by the changing circumstances of current history. The trick of humanistic problem-solving, at which the Ju|'hoan people are so good, is to value and use the best thinking and decision-making of each and every person living in the society today, as well as time-honored truths handed down over centuries. Decision-making among the Ju|'hoansi and other San peoples has long been by consensus. Each and every person's opinion is welcomed--male or female, old or young--towards the best course of the next group action. Rather than arrogating power to themselves, community leaders facilitate this kind of group process. It may take a group awhile to come to a decision, but when they do, it tends to stick because everyone has been involved in the process of creating it.”

If story and healing is indeed the engine for social cohesion among the San, what is your prediction for that society now that fewer stories are told and fewer dances take place that are initiated by the community?

“I am concerned, as are community members I've spoken to, at the apparent current loss of spiritual and cultural teachings and practices. I believe that these have dwindled, ultimately, due to the loss of land and autonomy over their own resources that San peoples have experienced. The Ju|'hoansi, like many San people, have expressed the wish for their languages to be revitalized by teaching their children, and by telling and recording and transcribing and translating stories. They also wish for their community healing ritual dance to continue to be practiced, and for its profound spiritual disciplines to be taught to the next generation. Projects to do just these sorts of things are springing up in many San groups, and organizations like our Kalahari Peoples Fund are assisting by supporting them. It means a great deal to San people to know that the great gifts of their culture are appreciated and can be put to valuable use by people beyond their own communities.”

4. You spoke of having to write in a different way for this memoir. Please elucidate and tell us what learnings you made as a writer, from this process.

“I learned, from the process of writing my memoir, just how valuable it can be to let time go by before attempting to extract lessons and conclusions from complex experiences. So much that I was able to put together from my years with the Ju|'hoansi only came together for me through the memoir-writing process. The "different kind of writing" (than academic writing) came to me through learning at last to leap beyond published predecessor sources and to value myself as the most reliable observational instrument I had. This process involved looking back at the journals I had written in the heat of the overwhelming moments and months of my fieldwork. and understanding them as illustrations of the more general comprehension about Ju/'hoan culture I arrived at after many years.”

5. Which is your favourite anthropological text, and why?

"My favorite anthropological text" is actually three related books. These are the two books on the Ju|'hoan people (earlier called !Kung) written by my mentor, Lorna Marshall, and the book The Harmless People by her daughter, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. I worked for Lorna Marshall for 25 years as a research assistant while she was writing The !Kung of Nyae Nyae and Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rites. I was closely involved in the many edits Lorna's writing went through in her pursuit of the perfect phrase to capture what she had experienced in Africa. My professional life was profoundly affected by these two mentors' strong command of evocative prose styling and effective use of the words of the English language. I was inspired to try to do the same myself in my own anthropological writing. I cannot think of a better set of anthropological books to start with, for anyone who wants to learn about the San peoples of the Kalahari.

Learn more about the wonderful work of the Kalahari People’s Fund here.